After more shifts than usual last week doing hospital chaplaincy, I have a few days off. I woke to spring sunshine and went for a walk in Nelson Woods — the woodland that adjoins our house. Last year I began a memorial garden there. The space is where I lay rocks or pine cones or other natural objects in my own ritual to honor patients whose deaths have particularly affected me. When I do that, I also symbolically release them. I turn the burden of sorrow into the blessing of memory.

Mind you, I no longer remember all the names except the most recent ones or the ones that really stand out. I do remember RB, who was my age, grew up in my Chicago neighborhood, and whose cousin I knew. That patient inspired me to begin this garden. Another stone is for R, who died in the pediatric emergency room on a night when I had to respond to three children’s deaths.

Today I lay a snail shell I happened to find in the woods to memorialize a patient who died of Covid-19, the first such death I handled. Many will remember that person, who functioned in a large network of people. Now I am a part of that group who mourn their passing.

I have never forgotten John Donne’s famous reflection that “any man’s death diminishes me” since I first read Donne decades ago. He wrote that in 1624 after recovering from an illness that was affecting fellow Londoners. As a chaplain who regularly meets people at the end of their lives, as well as their families, I am regularly diminished. Yet I have also learned that I am not called to cry for every single person. The psychological skill of boundary-setting has been challenging for me, a lifelong bleeding-heart liberal, but life-saving.

I can only read so many stories about people dying of Covid-19. I want those who have died to be mourned rightly by those with whose lives they are intertwined. But I also have my own business to attend to. In the hospital, I am called to another patient whenever the pager rings.

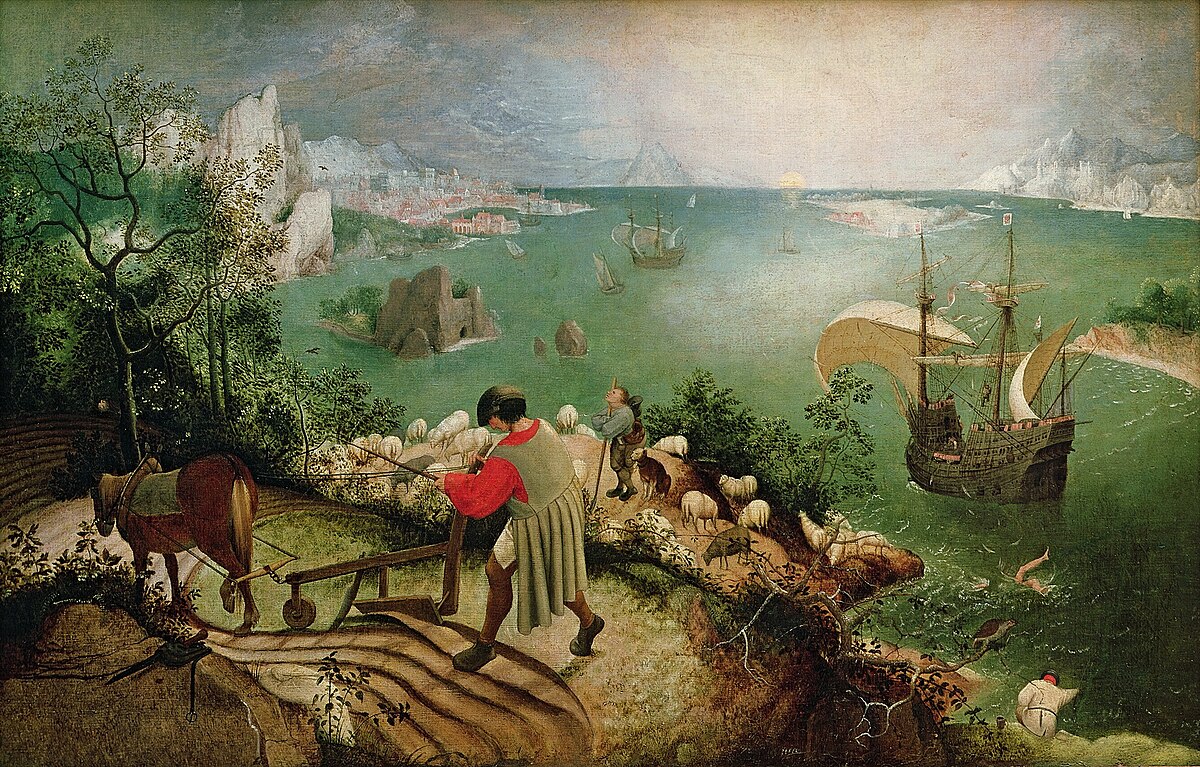

Another poem I read at the same time I studied John Donne’s devotional thought was Musee des Beaux Arts by W.H. Auden, written in 1938 as Europe was sliding into the global conflagration of WWII. Reflecting on the painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, the poet observes how in the face of a disaster — a boy falling from the sky — “dogs go on with their doggy life” and a ship at sea near the fallen figure “had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.”

We can mourn. We can remember. We can be diminished. We have somewhere to get to and are sailing, not always calmly, on.

Quaker query: How can I balance my diminishment with my need to sail on?

We bought this wooded property almost 20 years ago because we saw woodland wildflowers, delicate spring beauties prominent among them.

We bought this wooded property almost 20 years ago because we saw woodland wildflowers, delicate spring beauties prominent among them.